On October 3, 2025, Boko Haram fighters overran the Nigerian border town of Kirawa. They set fire to homes, a military barracks, and the palace of the district head. Over 5,000 residents fled into neighbouring Cameroon, some in trucks and others on foot. The local chief, Abdulrahman Abubakar, told Reuters, “I was left with no option but to flee to Cameroon.” At dawn, the town was already deserted. Boko Haram released videos showing its fighters chanting “victory belongs to God” as flames consumed the city. Senator Ali Ndume, representing Borno South, lamented the absence of security forces, pleading with the Federal government to deploy even “a platoon” to protect Kirawa and its neighbours. “There is no single military presence in Kirawa,” he told Leadership newspaper in frustration, pointing out that only vigilantes and hunters remain to face an insurgency now in its sixteenth year.

What happened in Kirawa is not an isolated tragedy. It is part of a continuing pattern of crimes against humanity that the International Criminal Court documented in 2022, when it accused both Boko Haram and Nigerian security forces of systematic crimes against civilians. The fall of Kirawa is yet another piece of evidence in this grim pattern.

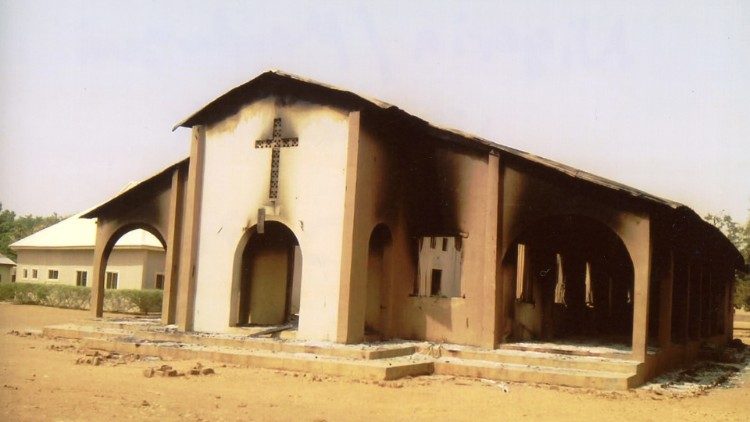

Christians, too, have suffered greatly during this ongoing period of violence. The number of Christian victims of Boko Haram is substantial; from worshippers murdered in Owo, Ondo State, to families slain in Yelewa, Benue; from priests and villagers abducted in Kaduna and Jos to men, women, and children murdered in Agamedu, Enugu State. It is undeniable that Christians have borne a heavy and tragic burden.

Advocacy groups such as Open Doors have described Nigeria as the deadliest place in the world for Christians, while the Nigerian-based Intersociety has reported more than 45,000 Christian deaths since 2009. These figures, echoed by U.S. Congressman Chris Smith, Canadian figures like Andrew Scheer, and television host Bill Maher, support a compelling narrative of “Christian genocide.” On October 3, 2025, Senator Ted Cruz also voiced his concerns on X, condemning the “mass murder of Christians” and calling for sanctions against Nigerian officials.

Yet, this framing represents only part of the truth. Muslims have also been killed in Borno and Yobe, with their mosques bombed, villages burned, and graves uncounted. Nigeria Watch estimates that over 208,000 Nigerians have died violently between 2006 and 2024, with nearly 12,000 in 2023 alone. ACLED confirms that many of these deaths occur in regions where the population is predominantly Muslim. As Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, editor of Boko Haram: Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria (2014), has shown, casualty counting in Nigeria is “methodologically fragile and politically charged.” Bodies are buried quickly, journalists often cannot reach the scenes, and families rarely disclose the faith of their deceased. This is why even the most respected datasets do not break down deaths by religion. What the data do reveal is geography: the highest tolls are in Borno and Yobe, predominantly Muslim states. To claim that the crisis is solely about Christians is to erase the Muslim dead. Denying the suffering of Christian victims is equally false.

Why does the “Christian genocide” narrative continue abroad? Part of the answer lies in the politicisation of religion itself. As Daniel Agbiboa and Benjamin Maiangwa argue in Boko Haram, Religious Violence, and the Crisis of National Identity in Nigeria (Oxford/UNU, 2014), the insurgency in Nigeria cannot be simplified to just a religious issue. It can be traced back to the mobilisation and politicisation of faith amidst structural poverty, corruption, climate shocks, and heavy-handedness by the state. Religion intensifies the divisions and justifies violence, but it does not fully explain the conflict. Portraying the killings as genocide solely against Christians misreads the underlying causes—and risks weaponising one community’s pain at the expense of another.

If these crimes are to stop, Nigeria and its partners must move from words to action. The first step is honesty. The Nigerian government should establish an independent and transparent system for documenting casualties that accepts uncertainty and aims to prevent inflating figures for advocacy. The second step is protection: every civilian life, whether in a church in Ondo or a mosque in Maiduguri, deserves equal security. The third step is accountability. There is abundant evidence that both Boko Haram and parts of Nigeria’s security forces have been involved in atrocities and impunity. The fourth step is investing in peace: creating jobs for Nigeria’s restless youth, promoting interfaith solidarity, and rebuilding trust in communities torn apart by suspicion.

International actors have expressed concern, but often in selective ways. For some, Nigeria illustrates a global “war on Christians.” Abuja may dismiss this rhetoric as exaggeration, helping the state avoid accountability. Advocacy networks, however, may be tempted to weaponise statistics. Of course, there is potential here: if global concern shifts from sensational figures to addressing key reforms — such as supporting peacebuilding, pressuring for security-sector accountability, and providing resources for displaced families — then voices abroad could still play a role in helping Nigeria heal.

The story of Kirawa demonstrates what is at stake. While Senator Cruz discusses sanctions in Washington, Senator Ndume pleads for soldiers in Borno. As advocacy groups debate genocide, villagers escape into Cameroon, their homes reduced to ashes. Christians and Muslims alike remain unprotected, their dead uncounted, their lives politicized for arguments not their own.

So, whose dead count? The Christians of Ondo, Benue, Kaduna, Jos, and Enugu? The Muslims of Borno and Yobe? Or the thousands of ordinary Nigerians who, regardless of their faith, are abandoned by the state meant to protect them? The truth is that every life matters. Every unrecorded death diminishes us all. Facts are precious. Arguments are important. But truth — hard, complex, unvarnished truth — must remain our compass.

While data remain unclear in Nigeria, numbers are weaponised abroad. So, until Nigeria learns to count its dead honestly and protect its living with determination, others will keep tallying and spinning them on its behalf.