For many decades, African Catholic Churches have faithfully celebrated the sacred liturgy with deep reverence and growing local participation. Yet, one troubling contradiction remains largely unexamined: while the Church in Africa is rich in human resources—young people, scientists, agronomists, chemists, theologians, and researchers—we still depend almost entirely on imported wine and other imported liturgical products for the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. This reality sadly raises a serious pastoral, theological, and socio-economic question: why, after so many years of inculturation discourse, can we not produce indigenous Eucharistic wine in Africa, and why are our churches largely silent on this possibility?”

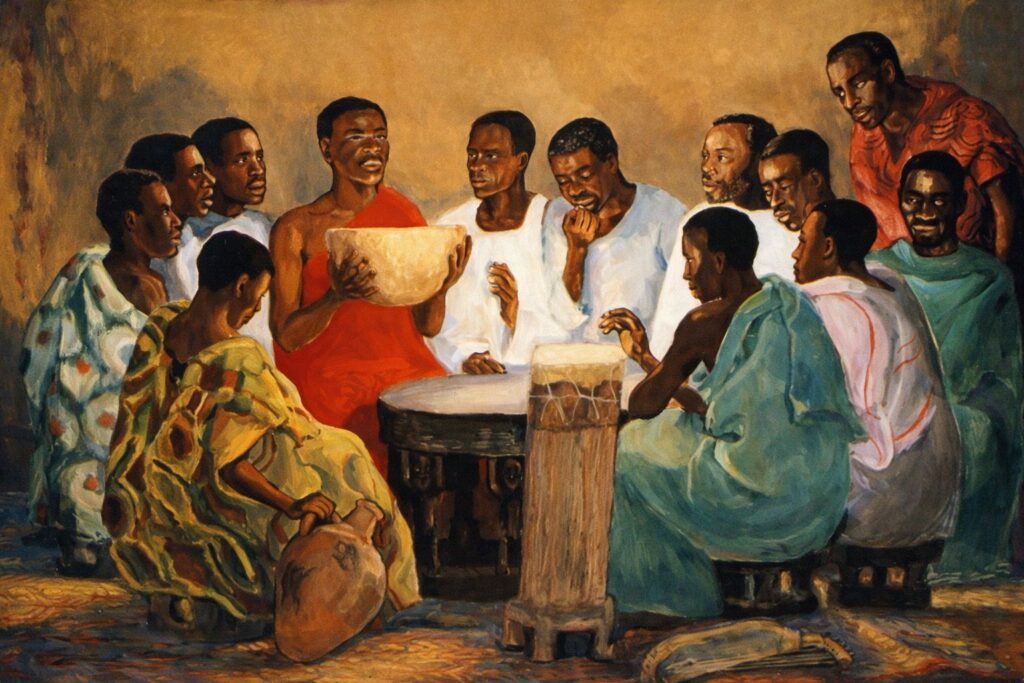

The Second Vatican Council stated emphatically that the liturgy is not meant to remain foreign to the people. Sacrosanctum Concilium teaches that the Church “does not wish to impose a rigid uniformity” and that provisions should be made for “legitimate variations and adaptations to different groups, regions, and peoples” (SC, no. 37–40). Inculturation, therefore, is not a favor granted to local churches; it is a theological imperative. Yet in practice, we often limit our view of inculturation to music, vestments, dance, and language, while leaving the material culture of the sacraments—especially the Eucharistic elements—almost entirely foreign.

After decades of inculturation discourse, the continued importation of Eucharistic wine exposes a troubling contradiction: Africa is trusted to receive the Eucharist but not yet trusted to produce what the Eucharist requires.”

On prescribed liturgical wine, for example, the Church teaches clearly that valid Eucharistic wine must be natural grape wine, unadulterated and fermented (cf. General Instruction of the Roman Missal [GIRM], no. 322; Code of Canon Law, can. 924 §3). This requirement does not demand importation. Grapes can be cultivated in many parts of Africa, and where climates are challenging, modern agricultural science offers solutions through controlled environments, hybrid vines, and viticultural research. Africa has universities, research institutes, and brilliant young scientists capable of meeting these standards—if only Church leadership would intentionally believe in their abilities and engage them.

Here lies a missed opportunity. By continuing to import Eucharistic wine, the Church unintentionally exports jobs, skills, and capital. We lament youth unemployment, brain drain, and economic dependency in our criticism of the political class, which has failed adequately to engage the youth. Yet, one of the most consistent components of Catholic worship—the wine for Mass—is rarely produced locally. Imagine diocesan or regional wineries owned or supervised by the Church, employing young agronomists, chemists, microbiologists, economists, and artisans. Such initiatives would not only guarantee liturgical authenticity and quality control but would also become centers of training, research, and employment.

By continuing to import Eucharistic wine, the Church in Africa unintentionally exports jobs, skills, and capital. This quiet dependency undermines our commitment to youth empowerment, scientific innovation, and economic dignity, even as the Eucharist we celebrate proclaims communion, participation, and shared responsibility.”

This is not without precedent. In Europe and most other parts of the world, as well as in the Americas, monasteries and dioceses have historically produced altar wine, hosts, vestments, candles, and liturgical books. These were not seen merely as economic ventures but as extensions of the Church’s sacramental life and stewardship. Why should Africa be different? Are we saying that African soil is holy enough to receive the Body and Blood of Christ, but not capable of producing the wine that, through consecration, becomes that Blood?

Moreover, the question extends beyond wine. The hosts we use are often imported; liturgical books, the missals, Bibles, ritual books, breviaries, etc., are printed abroad at high cost; even basic sacramental items are sourced externally. A truly indigenous Church must ask hard questions about self-reliance. Pope Paul VI, in Evangelii Nuntiandi, insisted that evangelization must touch “the criteria of judgment, the determining values, the points of interest, the lines of thought” of a people (EN, no. 19). Economic dependency in worship quietly shapes our ecclesial imagination, teaching us—perhaps unconsciously—that what is sacred must come from elsewhere.

Engaging youth and researchers in producing Eucharistic wine would also deepen catechesis. Young people would see that faith and science are not enemies, that laboratories, farms, and factories can serve the altar. This integration responds directly to Pope Francis’ call in Christus Vivit to trust young people with real responsibility and creativity in the life of the Church (CV, no. 203). It also resonates with Laudato Si’, which urges local solutions, respect for land, and sustainable economies rooted in community (LS, no. 179).

Liturgical groups—priests, liturgy committees, seminaries, and bishops’ conferences—must therefore move from lamentation to action. Feasibility studies can be commissioned, partnerships with Catholic universities formed, pilot vineyards established, and clear guidelines developed in fidelity to canon law and liturgical norms. What is lacking is not capacity, but vision and courage.

Importing Eucharistic wine decade after decade is not a neutral choice; it is a pastoral and prophetic failure that silently teaches Africa that what is sacred must always come from elsewhere.”

In conclusion, importing Eucharistic wine decade after decade is not a neutral choice; it is a pastoral and prophetic failure. If the Eucharist is truly the “source and summit of the Christian life” (LG, no. 11), then every dimension of its celebration—including its material elements—should reflect our commitment to dignity, participation, and responsible stewardship. Let us dare to believe that Africa can feed her own altar. Let us become indigenous not only in song and dance, but also in production, innovation, and shared prosperity—for the glory of God and the good of His people.